IMAGINARY MACHINE

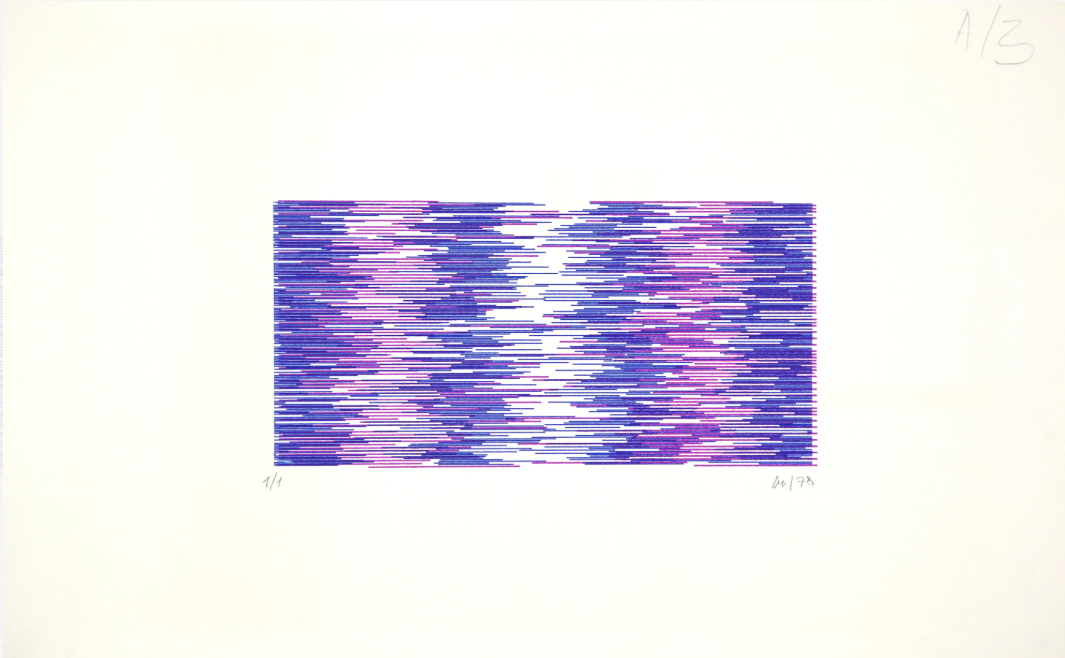

Vera Molnar (1924–2023) was a pioneer of digital and algorithmic art, whose practice intersected geometry, conceptualism, and emerging technologies. Widely recognized as one of the first artists to systematically explore rule-based image-making, Molnar laid the groundwork for what would later be called generative art—decades before digital tools became widespread. Her work is rooted in the tradition of geometric abstraction and shaped by the influences of artists like Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, and Paul Klee. Yet, she deliberately distanced herself from the dogma of Constructivism, carving out an individual position somewhere between anarchic systems and conceptual rigor.

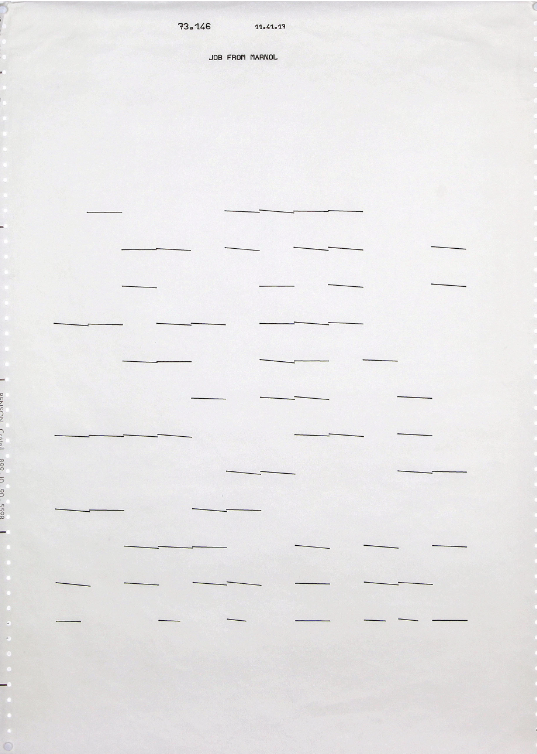

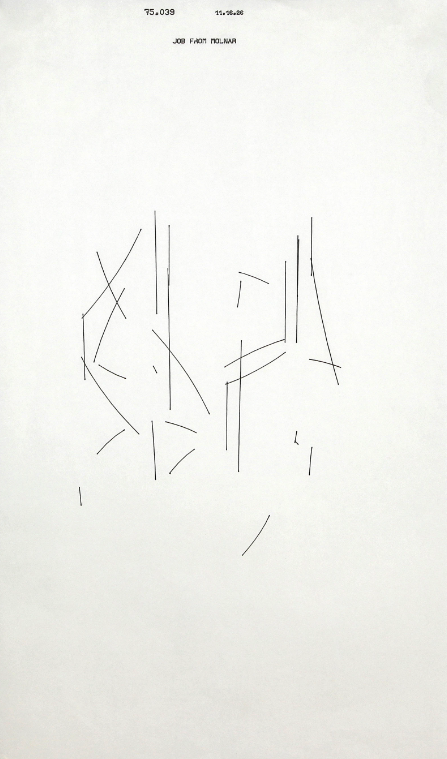

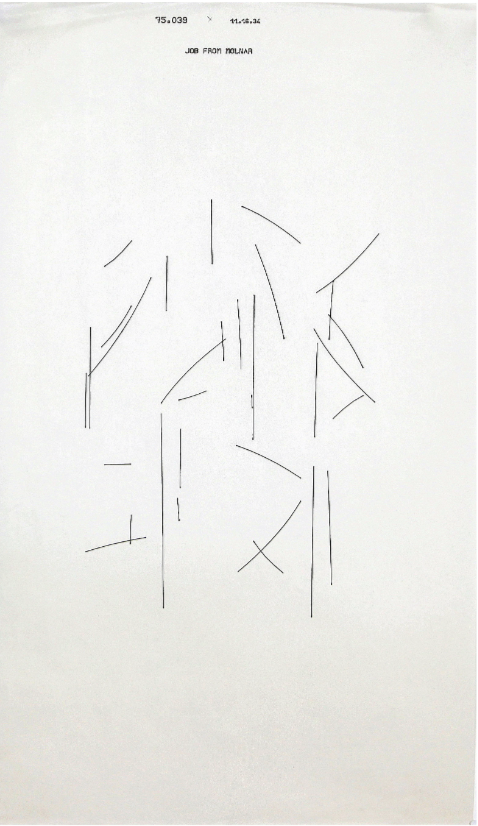

After moving to Paris in 1947, she became part of a vibrant network of artists experimenting with Concrete and Kinetic Art, including François Morellet, Julio Le Parc, and others. During the 1960s, she began developing her own visual systems using the most elementary means: paper, ruler, compass, and index cards. These early analog experiments were guided by sets of strict rules—geometric compositions defined by seriality, repetition, and variation. She was interested in creating images that appeared as if they were produced by a machine, even before she ever touched a computer.

This is where her concept of the “imaginary machine” (machine imaginaire) comes into play. Coined by Molnar herself, the term describes a fictional machine in her mind—an abstract entity she would mentally program with a system of rules and parameters to guide the creation of an image. The imaginary machine allowed her to simulate generative processes without technical means: it was a cognitive strategy, an internal engine of artistic production, grounded in logic and abstraction. This approach allowed her to distance herself from subjective expression and instead explore the aesthetic potential of constraint and variation.

In 1968, Molnar began working with computers at the Sorbonne, one of the first artists to do so. Using early mainframe systems and plotter printers, she translated her imaginary machine into real algorithms—often written in collaboration with computer scientists. Her interest was never in the medium itself, but in what it could offer to the systematization and extension of visual possibilities. The machine was a tool for thought, a way to push beyond intuition and enter new territories of form, rhythm, and randomness.

Molnar’s “imaginary machine” thus becomes a central metaphor in her artistic practice—one that continues to resonate in the context of contemporary digital and generative art. Rather than relying solely on technological novelty, her work consistently emphasized structure, critical distance, and conceptual clarity. Over decades, she remained committed to the core principles she had established early on: reduction, repetition, and visual logic—always open to disruption, error, and the aesthetic surprise that emerges from a calculated rule being slightly broken.

Today, Molnar is widely recognized as a visionary figure in the history of computational art. Her works—ranging from early plotter drawings to later digital prints—reveal a lifelong engagement with the tension between order and disorder, the hand and the machine, the imaginary and the real.